Plurality Of Digital Practices

Never has a technique or technology so intensified artistic practices in a way that is as dazzling as it is long-lasting, beginning with the fields of sound and image, which have been revolutionized profoundly; to the point that there is not a single work today without some digital component, as small as that may be.

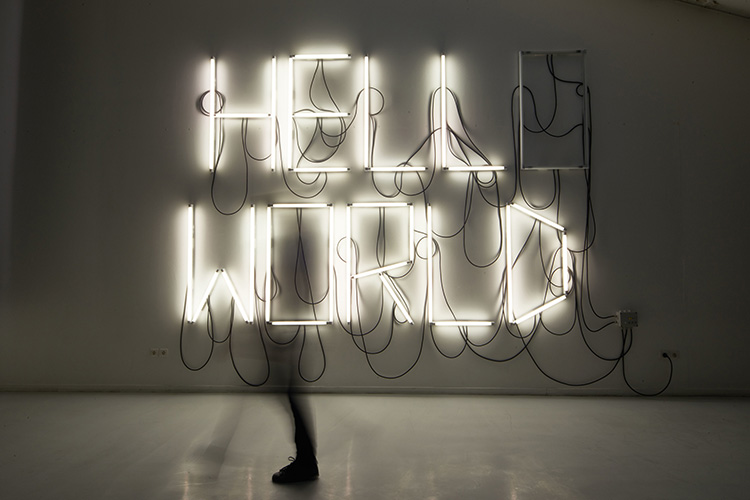

Hello world

Fabien Léaustic, Hello World, 2016, source Juan Cruz Ibanez.

Gone are the notebooks that began with "Dear diary". Today on YouTube, we reach the greatest number by exclaiming: "Hello world". Even the computer programs from the 1978 book, The C Programming Language by Brian Kernighan and Dennis Ritchie, were politely initialised with “hello world”. This did not escape the French artist Fabien Léaustic whose practice is often between art, science and technology. In 2016, Léaustic began to use this formula testifying to the proper execution of applications or scripts of the past forty years, on the walls of exhibition halls. All the characters are illuminated, but there is one, the first 'O', which turns on and off alternately. Hello World thus becomes Hell World. As if the wonderful world the giant digital companies are preparing for us could also turn into hell on earth. Let us recall Ridley Scott’s advertisement for Apple in 1984 with its slogan, “On January 24th, Apple Computer will introduce Macintosh. And you'll see why 1984 won’t be like ‘1984’”. The director and the brand refer to George Orwell’s book 1984, which he wrote in 1949. The writer paints a portrait of a society under surveillance that, ironically, we are perhaps preparing for in our immoderate use of the services offered to us. But how could George Orwell have anticipated this propensity that we all have to document, by our own accord, our lives with such precision?

From code to artwork

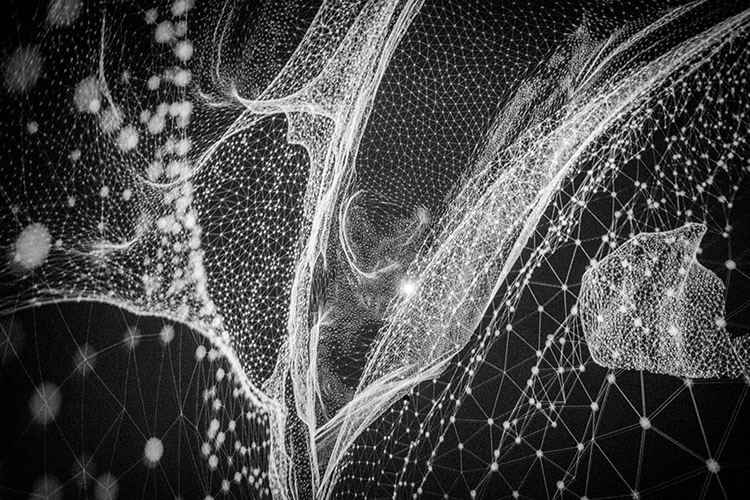

Anne-Sarah Le Meur, Rosespose_075, 2018, courtresy Galerie Charlot.

In 2013, the Prada Foundation of Venice re-enacted the historic exhibition When Attitudes Become Form that the independent curator Harald Szeemann conceived in 1969 at the Kunsthalle in Bern. In particular, the idea was that processes take precedence over results and, therefore, the unfinished could finally be celebrated. But what happened during the forty-four years that separated these two events? Code has intervened in all sectors of activity to impose and shape the work of urban planners, architects and designers in every field, even though it is generally hidden or simply incomprehensible to most of us. Some artists, such as Anne-Sarah Le Meur, have not escaped the call of the language of machines, who has been working year after year with the infinite variations that numbers allow. Here one thinks of the divine proportions of the ancients, although her work is exclusively abstract. Not to mention that she has eradicated any form of gesture to replace it with inspired movements, with relative freedom, through mathematics. It is the process of the executing code that creates the work that the artist can modify or interrupt at leisure in order to be, herself, surprised. When generating still images, these constitute as many unfinished stages towards the sublime, that so many artists, like Marc Rothko, whom Anne-Sarah Le Meur frequently refers to, have tried to reach.

Without beginning or end

fleuryfontaine, Index, 2017.

Generativity, in art, is an attitude that reinforces the essential of forms, specifically those which are inscribed in continuation, as is the case in the work of the Parisian artists Galdric Fleury and Antoine Fontaine, who together, compose the duo fleuryfontaine. Though they both studied architecture, a subject that fascinates them, they are not in the least attracted by the idea of designing buildings, except those likely to accommodate ideas or concepts. And here we think of the British architecture magazine Archigrami> of the 1960’s. The duo never stops proposing peregrinations within creations without beginning or end. In 2017, they focused on corridors through a generative installation entitled Index. The corridor, in appearance, is a place of passage that architects would free themselves of if only teleportation were possible. They are not places, by definition, since they serve rooms. And it is precisely in this organizing function that they become inseparable from the powers exercised by the heads of ministries or administrations, universities and prisons. These spaces that are corridors, without proper identities, are therefore interchangeable, as the fleuryfontaine creation shows us. And maybe that's why these places fascinate us, just as they have never ceased to fascinate generations of filmmakers, more than photographers. Because corridors are non-places whose uses are in the duration. This is the real subject of the work Index because it is infinite. When the paint or colours change, but the three-dimensional doors or sconces are similar, the machine simply chooses the locations. These artists are thus at the origin of an algorithmic as well as filmic framework, while the work continues to be ‘computed’ in their absence.

On immersion

Joanie Lemercier & James Ginzburg, Nimbes, 2014, coproduction SAT Montréal, production artistique Juliette Bibasse.

Immersion was already one of the main fields of investigation for experimental artists in the 1990’s. These latter expressed themselves mainly through dedicated events such as the International Symposium on Electronic Art (ISEA) of Montreal in 1995, from which the Society for Arts and Technology (SAT) emerged. In 2011 the Montreal SAT was equipped with a dome dedicated to 360 degree spherical projections. This encouraged contemporary artists like Joanie Lemercier and James Ginzburg to develop immersive experiences such as Nimbes (2014). The Satosphere can accommodate up to 350 people, so the experience is decidedly collective. The audience is invited to lie down comfortably since the show, in real time, is played above and all around. Patterns, fragments of nature and architecture intertwine with media types that combine photography with video, scanning and 3D modelling, so that a world, in total darkness, can literally take shape. The particles that rise bring us back to the gravity that constrains us, although it seems to fade over the experience as it is all-encompassing. In this creation, clues guide us towards dream, so that each and every one manages to give a meaning, which is ours alone, to this world whose story envelops us temporarily.

The virtual and gender

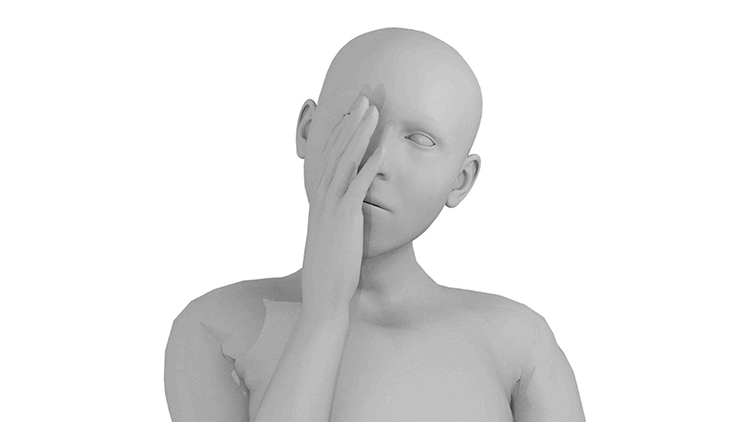

Judith Deschamps, Ne plus être dans votre regard, c’est disparaître, 2016.

Judith Deschamps grew up in the years 1990-2000, at which time, video games were all the rage and the figure of the avatar appeared. In 2016, on the occasion of the performance Ne plus être dans votre regard, c'est disparaître (To be no longer in your gaze is to disappear), she shows herself to the public of the Ricard Foundation alongside her avatar. The latter is imprecise in its gestures and movements if we consider the extreme realism of those we give life to today through our games consoles. But above all, what sets it against the characters who populate video games, is that it has no gender. And it is in this sense that it is, without being entirely, Judith Deschamps, who assumes the role of the interpreter during the performance. The avatar states "Just as Judith Deschamps did not choose to be a woman, I did not choose this state, I have not chosen to be artificial". The artist, translating into French the words of her virtual double, speaks for herself in the third person to develop a speech about identity while expanding it to the extreme as Queer theorists do. With Ne plus être dans votre regard, c'est disparaître, Judith Deschamps practices a form of reversal. Because it is she who makes the link between the being that she interprets and the public. In doing so, she questions gender through this other without gender, because artificial. This is how the virtual, having emerged in the field of art in the 1990’s, is no longer an end here but a means, encouraging us to consider social gender otherwise.

Another outlook

Rafael Rozendaal, Abstract Browsing, 2014, collection of Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam.

Addressing the Internet is a reminder that artists, in the art world, were the first to appropriate it with the emergence of the Web in the 1990’s, long before institutions ventured in or galleries sold work there. Already belonging to the second generation of artists who express themselves through networks, Rafael Rozendaal has been depositing his works online since the beginning of the 2000’s using a rather simple principle: by associating an idea with a form and an address. But it was in 2014 that he offered us another look at the pages that we know so well by developing an extension called Abstract Browsing to add to the Chrome browser. With this, all text or image content is replaced by saturated colour areas. The hidden structures of our favourite websites turn into so many abstract compositions that no painter could ever have imagined, not even Peter Halley. Because they are only the consequences of increased research efficiency. Yet, they did indeed become artworks on the walls of the Steve Turner gallery in 2016. The artist has selected the most surprising of these non-compositions to obtain large tapestries and Los Angeles art lovers were then afforded another look at what they thought they knew, here Gmail, there Twitter! The use of looms is not neutral if we consider the one invented by Joseph Marie Jacquard in 1801. Because it was ultimately ‘programmable’ thanks to a punch card that makes it a true ancestor of the mass memories composing the cloud of all our data, even before they are organized into pages.

Personal data

Varvara & Mar, Data Shop, 2017.

Talking about the Internet also means talking about our personal data, which interests so very many private and public companies. Data that they collect and usually exchange without our even noticing it and we must admit that we lack mental representations when it comes to large amounts of data. It is not the endless aisles of the few data centres that allow photography that are likely to improve our network vision of the incessant flow of our personal data. Some artists, like Varvara Guljajeva and Mar Canet, from the duo Varvara & Mar, are helping us to figure this out. The idea, with the installation Data Shop (2017), is to encapsulate their own data in cans to align them on the shelves of a reconstituted supermarket. This has the effect of recalling both Piero Manzoni's Merda d'artista (1961), for its resolutely personal character, and Andy Warhol’s Campbell soup cans accumulated in 1962. This is how we can imagine the market of our data going to the highest bidder. Which reminds us of the personal data of millions of Facebook users that Cambridge Analytica made available to politicians wishing to influence voters in 2015. Varvara & Mar therefore draw our attention to the value of the traces we leave that are none other than the consequences of our disinterested meanderings online. But also, the Internet of Things is looming with which companies are already planning to document, in order to profit from them, even the least of our actions.

In community

Émilie Brout & Maxime Marion, Lightning Ride, 2017, vidéo UHD, 7'40'', courtesy Galerie 22,48 m².

The Internet is also and especially mass content that the number of views validates, whereas never have the frontiers and the scope between artists and non-artists been so undefined. Content which, by its nature, draws the contours of addictive communities. YouTube is full of sequences whose strangeness challenges the artists of the generation of Émilie Brout & Maxime Marion. Together, they have appropriated sequences of those who, wishing to wear taser guns, have participated in certification sessions. The artists then slowed the scenes, giving them the appearance of oil paintings. More than the pictorial style, whose appearance strikes or seduces the retina, it is the attitudes of these volunteers to electrification in Lightning Ride(2017) that evokes the history of art. In particular, the representations of Saint Sebastian who, in the paintings of the Renaissance, never suffers despite the impressive number of arrows deeply penetrating his flesh. Condemned by Caesar, the saint addressing his own archers said: “AArchers, Archers, if you ever loved me, that your love I may know still, by measure of iron! I tell you, he who most deeply hurts me, most deeply loves me ”. This theatricality is reflected in Émilie Brout and Maxime Marion’s video-pictorial collage, both in the smiles effected so little by suffering at the moment of electric shock, as in the compassion of those who lower the volunteers to the ground.

Learning to see

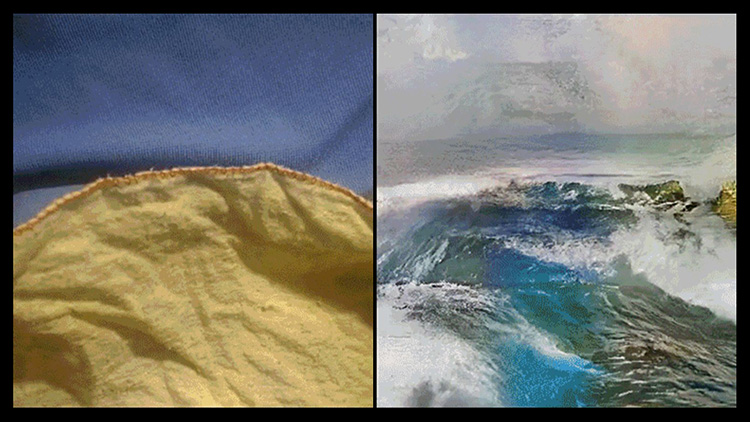

Memo Akten, Learning to see: Gloomy Sunday, 2017.

In 1997, an IBM computer won a chess game against a human, and not just any human, as it was Garry Kasparov. In 2015, a Google application won against a professional Go player. But what would happen, beyond the different periods, if these two artificial intelligences clashed? Probably nothing because the machines, from the research laboratory to the manufacturing plant, can do only what they have been taught, even though they do it so much faster and so perfectly. This is what Memo Akten’s work, Learning to see: Gloomy Sunday from 2017 tells us. No matter what the artist provides, it can only represent what it already knows. This is how a dust cloth becomes a seashore and a phone adapter becomes a rock caressed by waves. The Artificial Neural Network Learning to see: Gloomy Sunday was coached by the artist who ‘taught it to see’, hence the title of the work. For its part, the subtitle indicates the boredom that such a predictable intelligence would provoke, beyond the effect of surprise relative to its dexterity. There is something in this artwork that reassures us as a human, which is the creative superiority of the artist over the machine that, here however, works together. Without the human, the machine would not be of great use, neither in industry or in art. At a time when we have delegated our knowledge to servers and our intelligence to applications, the relationship we have with technologies that come together ¬– in art as in any other discipline – is that of interdependence.

Articles

- Plurality Of Digital Practices

- The Chroniques Biennial

- Ars Electronica 2018

- Montreal BIAN 2018

- Art In The Age Of The Internet

- Art Brussels 2018

- At ZKM in Karlsruhe

- Lyon Biennale 2017

- Ars Electronica 2017

- Digital Media at Fresnoy

- Art Basel 2017

- 57th Venice Biennial

- Art Brussels 2017

- Ars Electronica, bits and atoms

- The BIAN Montreal: Automata

- Japan, art and innovation

- Electronic Superhighway

- Lyon Biennale 2015

- Ars Electronica 2015

- Art Basel 2015

- The WRO Biennale

- The 56th Venice Biennale

- TodaysArt, The Hague, 2014

- Ars Electronica 2014

- Basel - Digital in Art

- The BIAN Montreal: Physical/ity

- Berlin, festivals and galleries

- Unpainted Munich

- Lyon biennial and then

- Ars Electronica, Total Recall

- The 55th Venice Biennale

- The Elektra Festival of Montreal

- Digital practices of contemporary art

- Berlin, arts technologies and events

- Sound Art @ ZKM, MAC & 104

- Ars Electronica 2012

- Panorama, the fourteenth

- International Digital Arts Biennial

- ZKM, Transmediale, Ikeda and Bartholl

- The Gaîté Lyrique - a year already

- TodaysArt, Almost Cinema and STRP

- The Ars Electronica Festival in Linz

- 54th Venice Biennial

- Elektra, Montreal, 2011

- Pixelache, Helsinki, 2011

- Transmediale, Berlin, 2011

- The STRP festival of Eindhoven

- Ars Electronica repairs the world

- Festivals in the Île-de-France

- Trends in Art Today

- Emerging artistic practices

- The Angel of History

- The Lyon Biennial

- Ars Electronica, Human Nature

- The Venice Biennial

- Nemo & Co

- From Karlsruhe to Berlin

- Media Art in London

- Youniverse, the Seville Biennial

- Ars Electronica, a new cultural economy

- Social Networks and Sonic Practices

- Skin, Media and Interfaces

- Sparks, Pixels and Festivals

- Digital Art in Belgium

- Image Territories, The Fresnoy

- Ars Electronica, goodbye privacy

- Digital Art in Montreal

- C3, ZKM & V2

- Les arts médiatiques en Allemagne

- Grégory Chatonsky

- Le festival Arborescence 2006

- Sept ans d'Art Outsiders

- Le festival Ars Electronica 2006

- Le festival Sonar 2006

- La performance audiovisuelle

- Le festival Transmediale 2006

- Antoine Schmitt

- Eduardo Kac

- Captations et traitements temps réel

- Maurice Benayoun

- Japon, au pays des médias émergents

- Stéphane Maguet

- Les arts numériques à New York