Montreal BIAN 2018

Created in 2012 by Alain Thibault, the International Digital Art Biennial (BIAN) assures the continuity of the Elektra festival initiated in 1999. It takes place in various venues, including the Society for Arts and Technology (SAT) and the Arsenal Contemporary Art. At the same time, there is also an exhibition of Rafael Lozano-Hemmer at the Museum of Contemporary Art (MAC) of Montreal.

Inside

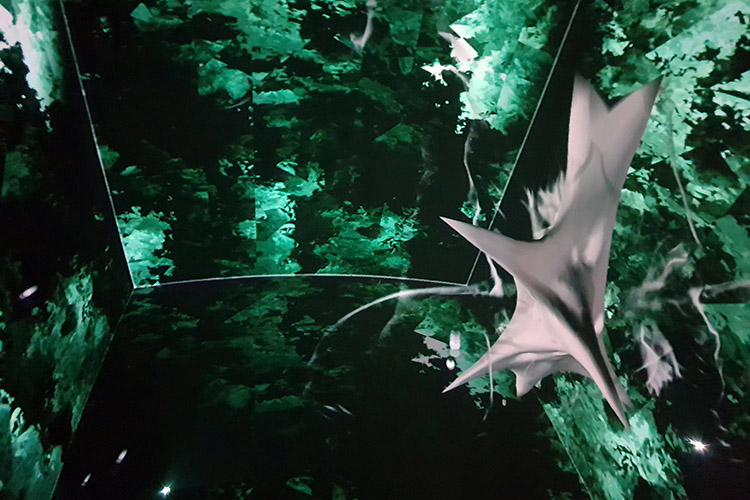

Alex Augier & Alba G. Corral, end(O), 2018.

TThe launching of this 2018 BIAN occurred at Society for Arts and Technology, emerging from the International Symposium on Electronic Arts (ISEA) organized by SAT director Monique Savoie in 1995. At the time, the event greatly participated in structuring what we used to name electronic arts. Time passes and practices evolve, although some like immersion remain. And it is to invest the dome that artists Alex Augier and Alba G. Corral came to Montreal. One is French and deals with the spatialized electronic sounds of howls that could come from tensions internal to the structure of this semi-sphere covering us. The other is Spanish and the extreme richness of her visual universes keeps us inside unidentifiable worlds where we cannot precisely understand the scales. The performance is entitled end(O), referring to the prefix “endo”, which means “inside”. Indeed, we are inside the artwork, which plays with our senses. In art history, attempts aiming to immerse the audience followed one another since parietal art. But we must acknowledge that immersion has lead to surge in interest for contemporary sound and visual artists.

Of language

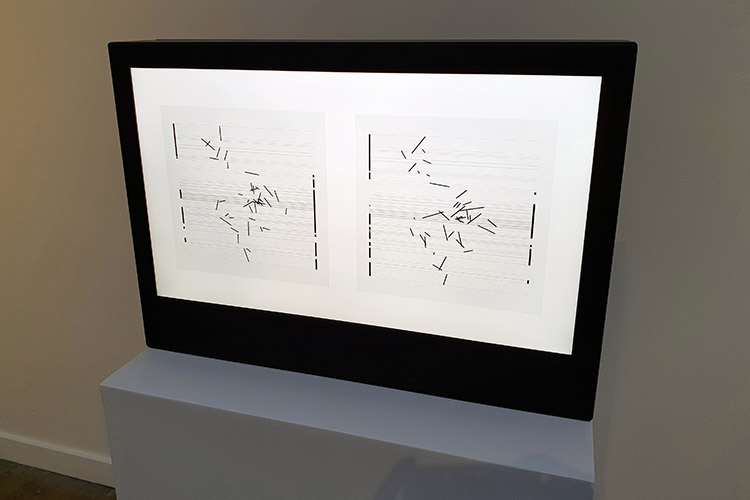

Manfred Mohr, “P1680-D”, Artificiata II, 2014-2015.

This fourth edition of the BIAN Montreal continues in the Arsenal where the main exhibition entitled Automata by curator Peter Weibel, who is also the founder of the Zentrum für Kunst und Medientechnologie (ZKM) in Karlsruhe, is held. It starts with artworks by Manfred Mohr of which we know the leading role concerning algorithmic practices in the context of art. In 1969 the artist, living and working in New York, conceived his first drawing with a computer. In the end of the 1960s, he wrote programs without any real-time viewing before printing. The late revelation of these images reminds us of the practice of an analogical photography where the pictures were revealed after. As time passes, Manfred Mohr has been able to adapt to other programming languages, while refining his vocabulary, unceasingly putting it at the service of an abstraction of infinite variations. Still in the plane, and more and more over time, his creations show us a world of instability in which details, whatever they are, have a meaning, a true importance.

Mirror effect

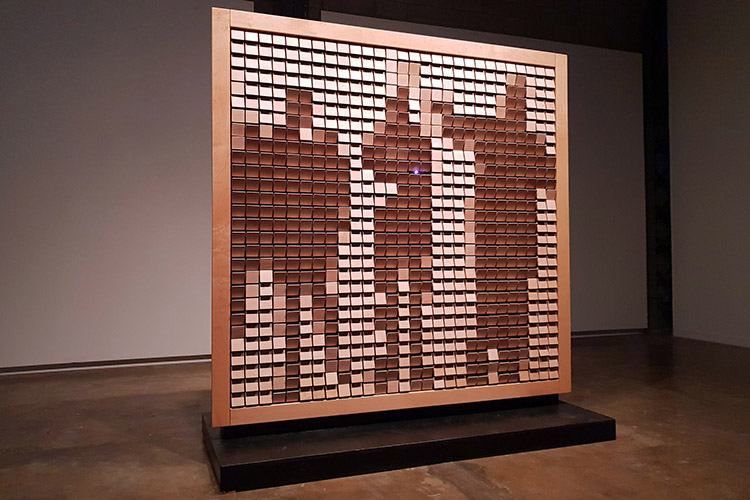

Daniel Rozin, Wooden Mirror, 2014.

As generative pieces guarantee surprise, installations are an incentive to action. It is the case with Daniel Rozin’s creation, a recent edition to his iconic artwork dating back to 1999: the Wooden Mirror. This artist, also living in New York, has unceasingly improved the first opus of a series of mechanical mirrors. But the idea remains the same: to take hold of a non-reflective material, wood, so that the audience is reflected by inevitably adopting postures of “entering the image”. The countless wooden tiles, depending on which position the mirror faces, are controlled by as many motors. Behind the mirror, the technology is not hidden to the curious audience. In the front of it, we are able to witness the continuing movements of the elements of a moving image accompanied by soft clinking. What is striking is the strange fluidity of the device. Its memory, as well as its resolution, is limited in its processing of distance. It has the effect of making us disappear from the image as we move farther away from it.

The letting go

Projet Eva, The Object Of Internet, 2017.

There is another apparatus, which is based around the use of moving mirrors, and it has been created by artist duo Projet Eva. Étienne Grenier and Simon Laroche invite us to put our heads inside what looks like an experimental machine as they are depicted in science-fiction. When the apparatus is switched on, our head seems to be separated from our body. The continuously moving mirrors reflect back many points of view. Once more, the artists play with our senses, as the device starts illuminating. The “letting go” is required as resistance is futile. We then think of out-of-body experiences that science ascribes to possible hallucinations. Still, we enter in a state of modified conscience, which can be compared to the one described by Brion Gysin’s Dreammachine (1960) users. Though the title given by Projet Eva, The Object of Internet, encourages us to consider the multiplication of points of view and comments that gravitate around our online profiles.

Masterpieces

Adam Basanta, All We’d Ever Need Is One Another, 2018.

Adam Basanta, another artist from Montreal, is most directly concerned in art history through an artwork entitled All We’d Ever Need Is One Anotheri>, an apparatus mobilizing two flat scanners, which only capture one another. The artist has automatized this task without any beginning, nor end, by injecting randomness into the process. He, himself, is always surprised every time an image emerges. The application compares it straight away to the files of a database gathering countless abstract paintings. The task of the color printer, which is part of the whole system, is to print images only when they resemble masterpieces very closely. Would it be, far beyond the technological achievement, a form of criticism against artists that follow trends instead of initiating them? Unless it is a criticism of the art market that tries to reassure while it is about speculating by limiting the risks. The idea of a device being able to make art without any artist is disturbing. As if art was another on demand service that would only need to be activated!

Simulating the living

Cod.Ac, πTon, 2017.

The BIAN Montreal is an extension of the Elektra festival, initially based on audiovisual performances. Thereby, several performances take place during the Automata exhibition’s inauguration. Among these, we notice the intervention of Cod.Act. Entitled πTon, it alludes to mathematics, or more generally science, with the number pi preceding the syllable “ton”, so that we think of the python. Indeed, what faces us has the appearance of a gigantic invertebrate. The beast wakes up when the audience gathers around it. Four performers are here, although we do not exactly understand their role. Are they here to tame it? Unless it is more of a sort of ritual! The various sounds produced by the beast add to the strangeness of the scene. But the contortions are what surprise, or even fascinate the audience. They are similar to that of constrictor snakes, which suffocate their victims. But there is no prey here, as the beast, or more exactly its ersatz, moves under the control of some algorithms. We ought to remember that Python is also the name of a programming language authorizing the simulation of the living.

The uncanny valley

Freeka Tet, Uncanny Valley, 2018.

Next there isFreeka Tet’s Uncanny Valley performance, the title recalls the text that Japanese roboticist Masahiro Mori published in 1970. He wrote that a non-humanoid robot easily generates empathy. While, in the case of an extreme resemblance with humans, we might be terrified by focusing on the tiny details, encouraging us to suspect its non-humanity. As for Feeka Tet, he films himself throughout his performance. But he adds real-time effects that provoke terror. In his face distorted by the glitch, a monstrous form emerges. Electronic music composed of accidents accompanies the image’s strangeness. This performative approach of the selfie, in the era of the general using of real-time image processing applications is interesting. Indeed, it goes against our desire of usually embellishing our image. The extreme darkness that appears through these multiple faces is like that which ceaselessly erodes Dorian Grey’s portrait. We are witnesses, frightened at the idea that these degradations would affect us by revealing the worst lying dormant in every of us.

Shadow’s memory

Rafael Lozano-Hemmer, Bifurcation, 2012.

The idea that image could reveal what is usually hidden from us is verified in the Contemporary Art Museum of Montréal which dedicates a monographic exhibition to Rafael Lozano-Hemmer. From afar, we see the image, or more precisely the silhouette of a tree imperceptibly twirling on itself. As if gravity, holding it to the ground, has been replaced by a virtual thread. Getting closer, we realize that it is the entire shadow of a branch hanging by a true thread. Regarding the movements of the shadow that is associated with it, the inherent breeze of the moving audience has an influence on the branch. Rafael Lozano-Hemmer likes the silhouettes, because they synthesize the shapes of the bodies or objects that they represent. But it appears to us that, in the case of Bifurcation installation, the silhouette is more detailed than the object to which it is associated. As if it was the extended memory of a branch, which, without any augmentation, would tell noting about the tree it comes from. The use of digital, in art, often allows the extension of the real with some stories that interrogate us, and, sometimes, transport us.

Articles

- Paris Photo

- Art, technology and AI

- Immersive Art

- Chroniques Biennial

- 7th Elektra Biennial

- 60th Venice Biennial

- Endless Variations

- Multitude & Singularity

- Another perspective

- The Fusion of Possibilities

- Persistence & Exploration

- Image 3.0

- BioMedia

- 59th Venice Biennale

- Decision Making

- Intelligence in art

- Ars Electronica 2021

- Art & NFT

- Metamorphosis

- An atypical year

- Real Feelings

- Signal - Espace(s) Réciproque(s)

- On Combinations at Work

- Human Learning

- Attitudes and forms by women

- Ars Electronica 2019

- 58th Venice Biennale

- Art, Technology and Trends

- Art in Brussels

- Plurality Of Digital Practices

- The Chroniques Biennial

- Ars Electronica 2018

- Montreal BIAN 2018

- Art In The Age Of The Internet

- Art Brussels 2018

- At ZKM in Karlsruhe

- Lyon Biennale 2017

- Ars Electronica 2017

- Digital Media at Fresnoy

- Art Basel 2017

- 57th Venice Biennial

- Art Brussels 2017

- Ars Electronica, bits and atoms

- The BIAN Montreal: Automata

- Japan, art and innovation

- Electronic Superhighway

- Lyon Biennale 2015

- Ars Electronica 2015

- Art Basel 2015

- The WRO Biennale

- The 56th Venice Biennale

- TodaysArt, The Hague, 2014

- Ars Electronica 2014

- Basel - Digital in Art

- The BIAN Montreal: Physical/ity

- Berlin, festivals and galleries

- Unpainted Munich

- Lyon biennial and then

- Ars Electronica, Total Recall

- The 55th Venice Biennale

- The Elektra Festival of Montreal

- Digital practices of contemporary art

- Berlin, arts technologies and events

- Sound Art @ ZKM, MAC & 104

- Ars Electronica 2012

- Panorama, the fourteenth

- International Digital Arts Biennial

- ZKM, Transmediale, Ikeda and Bartholl

- The Gaîté Lyrique - a year already

- TodaysArt, Almost Cinema and STRP

- The Ars Electronica Festival in Linz

- 54th Venice Biennial

- Elektra, Montreal, 2011

- Pixelache, Helsinki, 2011

- Transmediale, Berlin, 2011

- The STRP festival of Eindhoven

- Ars Electronica repairs the world

- Festivals in the Île-de-France

- Trends in Art Today

- Emerging artistic practices

- The Angel of History

- The Lyon Biennial

- Ars Electronica, Human Nature

- The Venice Biennial

- Nemo & Co

- From Karlsruhe to Berlin

- Media Art in London

- Youniverse, the Seville Biennial

- Ars Electronica, a new cultural economy

- Social Networks and Sonic Practices

- Skin, Media and Interfaces

- Sparks, Pixels and Festivals

- Digital Art in Belgium

- Image Territories, The Fresnoy

- Ars Electronica, goodbye privacy

- Digital Art in Montreal

- C3, ZKM & V2

- Les arts médiatiques en Allemagne

- Grégory Chatonsky

- Le festival Arborescence 2006

- Sept ans d'Art Outsiders

- Le festival Ars Electronica 2006

- Le festival Sonar 2006

- La performance audiovisuelle

- Le festival Transmediale 2006

- Antoine Schmitt

- Eduardo Kac

- Captations et traitements temps réel

- Maurice Benayoun

- Japon, au pays des médias émergents

- Stéphane Maguet

- Les arts numériques à New York