58th Venice Biennale

The main theme of this 58th Venice Biennale was entrusted to the American curator Ralph Rugoff. Its title, May you live in interesting times, appears to us as an injunction to appreciate the world as it is in observing it. Then the question of points of view arises!

Lara Favaretto, Thinking Head, 2017-2019.

To live in the present time, as Ralph Rugoff, who usually directs the Hayward Gallery in London, encourages us to do, is also to accept extreme complexity. And that may be the reason why he asked Lara Favaretto to plunge the central pavilion into a thick fog so as to mask its outlines. Fujiko Nakaya, already did this with the Pepsi Pavilion of the Osaka World Expo in 1970. But there is, fortunately, no patent on the use of fog in art. Although the times are different, there are some points in common since the end of the 1960’s corresponds with the first craze of the art scene for the premises of the technologies that the director of the Hayward Gallery has this year put in the spotlight.

Intangible

Ryoji Ikeda, spectra III, 2008-2019.

Ralph Rugoff also asked the artists to present two works with very distinct forms to exhibit some in the Giardini and others in the Arsenale, as if to emphasize the diversity of points of view, even via a single look. Ryoji Ikeda accepted the challenge by offering two installations, one of which is entitled spectra III in the central pavilion. It is a corridor whose white light dazzles us so much that we protect ourselves with our hands, as though as not to observe the unobservable. This excess might suggest the mass of information that daily overwhelms us, sometimes preventing us from taking the time to make a personal opinion about the society in which we play a part. The extreme light of this passage inevitably leads to an elsewhere that can also illustrate the inexorable end that we refuse to consider by building the mental images of spaces where the body would be superfluous.

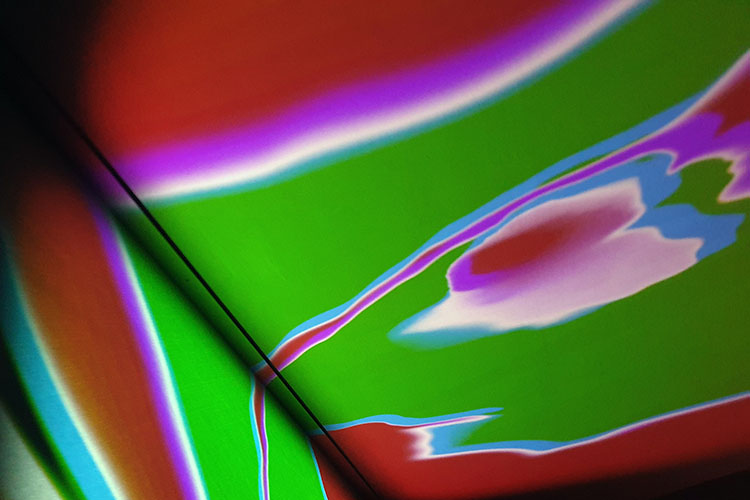

Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster, Endodrome (scenography element) 2019.

It is with the installation Endodrome by Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster that we experience the loss of the body by first being invited to sit at a table and then to put on a virtual reality headset. For the next eight minutes we are immersed in a universe in a gaseous state, without any gravity or apparent limits, until we realize that we can act on its form with movements, unconscious at first, of the head. We can create spirals that immediately become self-sustaining as do smoke puffs in the enclosed environments of interiors. Nothing in our field of vision indicates reality as we know it, including the absence of a body that is a prisoner in its sitting position in the old rope factory of the Venice Arsenal. The rules of the game having been defined by the artist, it is a kind of interior spectacle in which we actively participate that is played out to marvel us. It is a state of consciousness modified by the very images that we initiate while suspending control.

Larissa Sansour, A Monument for Lost Time, 2019.

Immateriality, in the Giardini, is not just virtual if one considers the installation A Monument for Lost Time by Larissa Sansour in the Danish pavilion. Because the object that we observe, even carefully, does not yield any information, neither about its shape or its thickness and changing one’s point of view by contorting oneself does not change anything. Is it a disc or rather a sphere? Never, without going beyond the limit that forbids our approach, will we know. What we learn is that the object, the very existence of which appears to us in suspense, has been covered with a particularly dull black. This painting, eager for light and summoning the sublime, is called Black 2.0 and is available online. But it must be confirmed that we are not Anish Kapoor. Recall that the latter is the patent owner of the 'blackest black of the world' that other artists and companies also claim. Art, the sublime, industry and trade, have never gotten along together so well. While in Venice spectators are still wondering about the state of the object that masks such a peculiar texture.

Time, history and staging

Laure Prouvost, Deep See Blue Surrounding You, 2019.

"In the next century, Venice will probably be submerged", exclaims Ralph Rugoff in an interview with The Art Newspaper when he discusses the consequences of global warming both on territories and populations. So, Laure Prouvost took the lead by partially flooding the floor of the French pavilion with a layer of resin. But the thin layer of blue has also frozen time by imprisoning rubbish, plants and shells among bits of outmoded electronics. A boon for underwater archaeologists of the next century if nothing is tempted to avoid the worst. The perfectly smooth surface of the floor appears to us in opposition to the organic matter or damaged objects that it contains within it. The electronic remnants of the installation Deep See Blue Surrounding You, which in such a short time have lost all of their useable value, testify to a form of acceleration of time. They are surrounded by cigarette butts that further reinforce their total lack of value. But from this disparate and frozen set a form of nostalgia emerges, which is that of suspended time.

Christian Marclay, 48 War Movies, 2019.

Christian Marclay takes another look at time by assembling war movies. The sequence 48 War Movies has no real beginning or end. It testifies, by its cacophony, of the murderous follies of different times. When we know the inexorable progression of nationalisms that history teaches us announce wars, deaths and other displacements of populations trigger in their turn elsewhere and otherwise the recesses of identity. This creation by Christian Marclay, whose work usually revolves around the notion of appropriation, is as hypnotic as it is deafening. Of the 48 films of reconstructed wars, we only perceive a form of synthesis that fascinates us, especially when we are lucky enough to have only known war through movies, series, documentaries or the news. Can we, then, appreciate these times of peace? Something which not everyone can enjoy when our countries are also involved in the arms trade!

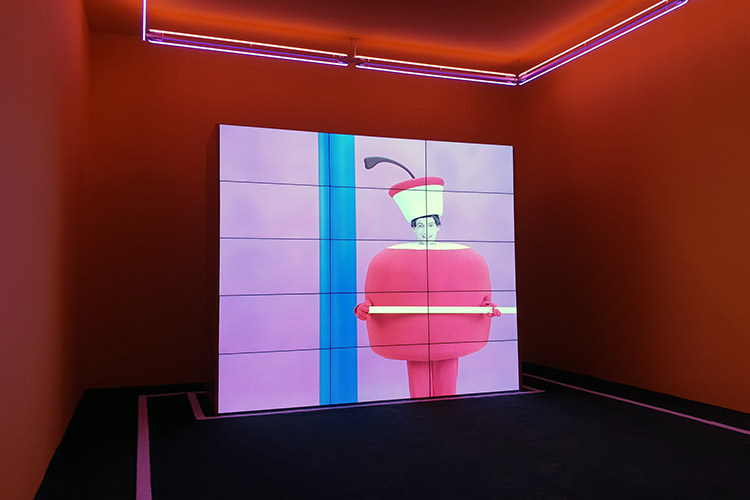

Alex Da Corte, Rubber Pencil Devil, 2019.

It is then that one perceives the possible cynicism of Ralph Rugoff that artists like Alex Da Corte treat with humour by designing small sequences whose burlesque attributes conjure silent films, while the perfectly groomed aesthetic of the 57 sequences of the installation Rubber Pencil Devil evokes that of television, and more generally advertising. Everything is too good to be true in this world where colours come together so perfectly. However, the American artist, whose studio looks like a film set, applies almost no effect to the scenes he shoots, going so far as to play in some of them himself. Humour, which in television as in advertising is a source of income, is very present. The real here, is only interpreted as it is done in the theatre to make us forget the sad reality of our sometimes grey lives. Beyond the video image, there are neon lights just as colourful and just as compelling as those we find in urban advertisements. Everything, in Alex Da Corte’s approach, is a matter of staging where chance, at least in appearance, never invites itself. But do we not also put our lives on social media, especially when we find ourselves in this idyllic setting that Venice offers and where selfie-poles are legion?

A few tales

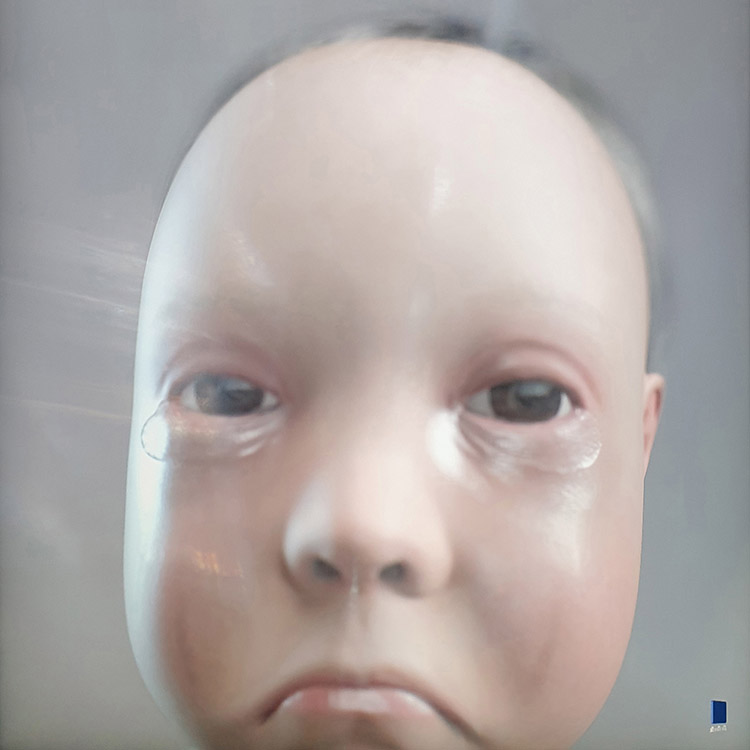

Ed Atkins, Old Food (detail), 2017-2019.

Ed Atkins' aesthetic is that of three-dimensional renderings that exist only in machines. With his Old Food series presented at the Arsenale, he tells little stories that intermingle with each other to establish a kind of tale. On the screen, we notice a baby that we learn was designed in the image of the artist. It cries incessantly with the long sobs of an adult. As if it could not forgive itself for the faults it probably hasn’t yet committed. It has a strange presence, reminiscent of the polychrome sculptures of crying virgins by Pedro de Mena from 17th-century Spain. The use of the three dimensions, in both cases, adds a supplementary soul to these representations of beings in tears. The groans of this infant that nothing can comfort are those of the artist himself. This has the effect of increasing the strangeness of the scene in which a man of a mature age follows. He too is absolutely sad and seems just as inconsolable. His voice is similar, so we imagine him at different ages of a life without redemption.

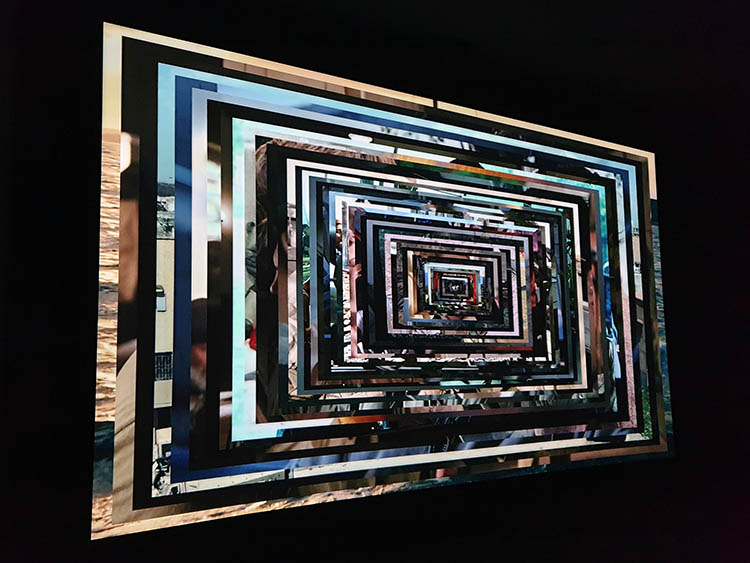

Jon Rafman, Dream Journal, 2016-2019.

Other artists at this 58th Venice Biennale are particularly fond of the aesthetics of computer-generated images. The Canadian Jon Rafman is one of those of his generation that Ralph Rugoff brought to Venice this year. His style is somewhat hobbyist, as is the trend in the world of art, unlike the so perfect 3D universe of animation films and video games. That is, bodies, for example, do not really have weight, as in dreams. A lack which, in the case of Dream Journal is quite suitable since it is a story revolving around dreams, each one stranger than the next. The sequences are typical of a form of automatic writing dear to the surrealists who already knew how to free themselves from the binding limits of reality. Thus, among the protagonists of a story where curiosities follow each other, a young boy has neither torso nor arms, and monsters rub shoulders with humans that at times happily overlap. There is much material here for psychoanalysts to study, who are also fond of contemporary artistic forms.

The role of machines

Sun Yuan & Peng Yu, Can’t Help Myself, 2016.

Machines are also honoured in the selection of the American curator. Like the totally autonomous industrial robot that artists Sun Yuan & Peng Yu put to work in the central Giardini pavilion. Its task is as simple as it is repetitive because, equipped with a kind of squeegee, it must contain the puddle of a reddish liquid within its scope of action. Its mission is futile since it is ‘condemned’ until the end of the Biennial to clean up what looks like blood here, to then stain the soil there. But it is unaware of this and that is what opposes machines to humans. This robot, passing from the world of industry to that of art, is observed differently. Its usefulness is aesthetic and the vanity of its mission can encourage us to relativize the importance of the actions or rituals that we sometimes repeat without asking too many questions. As for the idea that this reddish liquid could be spilled blood that a device could not contain, one thinks then of the atrocities of the world that one would like to silence but which, always, end up being revealed.

Shu Lea Cheang, 3X3X6, 2019.

While the robot of the installation Can’t Help Myself remains indifferent to our presence, it is not the same within the Palazzo delle Prigioni because the artist Shu Lea Cheang has installed a monitoring device that continuously scrutinizes all our actions and gestures. The palace, well before hosting the exhibition 3X3X6 of the Taiwan Pavilion, was a prison connected to the Palazzo Ducale by the famous Bridge of Sighs. The libertine writer Giacomo Casanova stayed there and the Taiwanese artist, living and working in Paris, was inspired to stage the stories of a dozen people who were imprisoned for their sexual behaviour, which was considered ‘deviant’, because surveillance and control often go hand in hand. States that invest heavily in technologies that are constantly renewed to monitor the smallest of our activities, also consider themselves the guarantors of morality. But that is without counting on social media to liberate speech for better and for worse. In the end, for this 58th edition of the Venice Biennale, there are no major societal issues that are left unaddressed.

Articles

- Paris Photo

- Art, technology and AI

- Immersive Art

- Chroniques Biennial

- 7th Elektra Biennial

- 60th Venice Biennial

- Endless Variations

- Multitude & Singularity

- Another perspective

- The Fusion of Possibilities

- Persistence & Exploration

- Image 3.0

- BioMedia

- 59th Venice Biennale

- Decision Making

- Intelligence in art

- Ars Electronica 2021

- Art & NFT

- Metamorphosis

- An atypical year

- Real Feelings

- Signal - Espace(s) Réciproque(s)

- On Combinations at Work

- Human Learning

- Attitudes and forms by women

- Ars Electronica 2019

- 58th Venice Biennale

- Art, Technology and Trends

- Art in Brussels

- Plurality Of Digital Practices

- The Chroniques Biennial

- Ars Electronica 2018

- Montreal BIAN 2018

- Art In The Age Of The Internet

- Art Brussels 2018

- At ZKM in Karlsruhe

- Lyon Biennale 2017

- Ars Electronica 2017

- Digital Media at Fresnoy

- Art Basel 2017

- 57th Venice Biennial

- Art Brussels 2017

- Ars Electronica, bits and atoms

- The BIAN Montreal: Automata

- Japan, art and innovation

- Electronic Superhighway

- Lyon Biennale 2015

- Ars Electronica 2015

- Art Basel 2015

- The WRO Biennale

- The 56th Venice Biennale

- TodaysArt, The Hague, 2014

- Ars Electronica 2014

- Basel - Digital in Art

- The BIAN Montreal: Physical/ity

- Berlin, festivals and galleries

- Unpainted Munich

- Lyon biennial and then

- Ars Electronica, Total Recall

- The 55th Venice Biennale

- The Elektra Festival of Montreal

- Digital practices of contemporary art

- Berlin, arts technologies and events

- Sound Art @ ZKM, MAC & 104

- Ars Electronica 2012

- Panorama, the fourteenth

- International Digital Arts Biennial

- ZKM, Transmediale, Ikeda and Bartholl

- The Gaîté Lyrique - a year already

- TodaysArt, Almost Cinema and STRP

- The Ars Electronica Festival in Linz

- 54th Venice Biennial

- Elektra, Montreal, 2011

- Pixelache, Helsinki, 2011

- Transmediale, Berlin, 2011

- The STRP festival of Eindhoven

- Ars Electronica repairs the world

- Festivals in the Île-de-France

- Trends in Art Today

- Emerging artistic practices

- The Angel of History

- The Lyon Biennial

- Ars Electronica, Human Nature

- The Venice Biennial

- Nemo & Co

- From Karlsruhe to Berlin

- Media Art in London

- Youniverse, the Seville Biennial

- Ars Electronica, a new cultural economy

- Social Networks and Sonic Practices

- Skin, Media and Interfaces

- Sparks, Pixels and Festivals

- Digital Art in Belgium

- Image Territories, The Fresnoy

- Ars Electronica, goodbye privacy

- Digital Art in Montreal

- C3, ZKM & V2

- Les arts médiatiques en Allemagne

- Grégory Chatonsky

- Le festival Arborescence 2006

- Sept ans d'Art Outsiders

- Le festival Ars Electronica 2006

- Le festival Sonar 2006

- La performance audiovisuelle

- Le festival Transmediale 2006

- Antoine Schmitt

- Eduardo Kac

- Captations et traitements temps réel

- Maurice Benayoun

- Japon, au pays des médias émergents

- Stéphane Maguet

- Les arts numériques à New York