Art, technology and AI

Three exhibitions are simultaneously exploring the use of technology in art, including digital and AI, within French museums: two at the Musée d'Art Contemporain in Lyon and one at the Jeu de Paume in Paris.

At MAC Lyon

Jeffrey Shaw & Dirk Groeneveld, The Legible City, 1988-1991. ZKM, Center for Art and Media, Karlsruhe. Source Lionel Rault.

The Musée d'Art Contemporain de Lyon, directed by Isabelle Bertolotti, is currently presenting two exhibitions featuring works brought together by technology. The first, by curator Matthieu Lelièvre entitled Univers Programmés, focuses on the relationship between art and technology over time, while the second, Échos du passé, promesses du futur by curator Marilou Laneuville, questions the relationship between technology and nature. In Univers Programmés, we discover Jeffrey Shaw and Dirk Groeneveld's interactive installation The Legible City, dating from 1988-1991, which allows visitors to discover the districts of several cities by means of their three-dimensional typographic representations, while pedaling on an exercise bike. An iconic digital piece that has a rightful place in contemporary art.

Kolkoz, Film de vacances, Hong Kong, 2016. Collection MAC Lyon.

Equally three-dimensional and already historic is the Kolkoz video installation from the Film de vacances series, dating from 2016. Everything in it is polygonal, from the film footage of Samuel Boutruche and Benjamin Moreau's trip to Hong Kong to the volumes of the sculpture featuring them. It's as if the whole had been extracted from the virtual by the artists. It's fortunate that this installation has been acquired by the Musée d'Art Contemporain, whose commitment to technology dates to the third Lyon Biennial in 1995.

Eva & Franco Mattes, Half Cat, 2020. Courtesy the artists & Apalazzo Gallery. Source Lionel Rault.

Let's step into the 2020s with Eva & Franco Mattes' sculpture Half Cat, depicting a two-legged cat. The atrophied feline has a history that recalls both the anomalies of Google Street View and the imagination of generative artificial intelligences, in this art world where artists only wait for the unexpected, when they don't provoke it.

Constant Dullaart, Accepting the Job, 2023. Courtesy the artist & Office Impart, Berlin. Source Lionel Rault.

Constant Dullaart's sculpture of a handshake, Accepting the Job (2023), evokes the standardized imaginary of the corporate world. And where the improbable tangle of fingers betrays the difficulty yesterday's AIs had in representing hands. But in what fields, and for how long, will we be able to reassure ourselves with qualities that are specifically human?

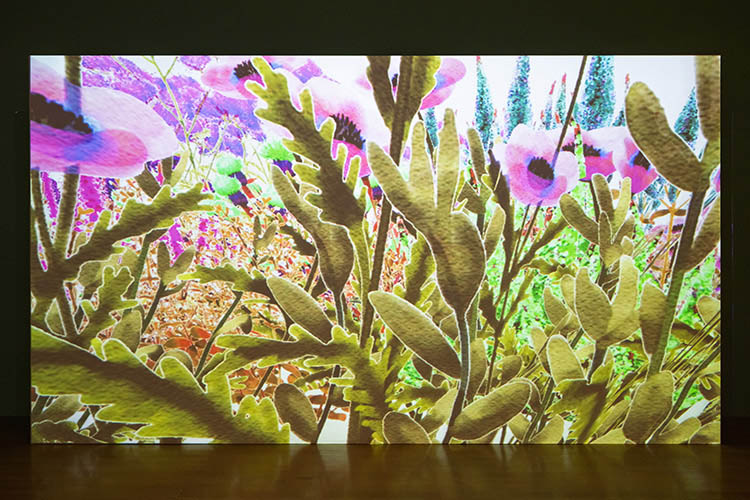

Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg, Pollinator Pathmaker, 2023. Serpentine & LAS Editions, Source Lionel Rault.

Meanwhile, the Échos du passé, Promises of the Future exhibition explores the living world with creations such as Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg's Pollinator Pathmaker (2023). This large-scale project combines gardens in the ground with virtual online gardens. Places that reconcile nature and artifice, designed for pollinating insects, as evidenced by the colorful works invoking the diversity of animal visions.

Léa Collet, Digitalis, 2023-2024. Production Le Fresnoy & fondation Neuflize OBC

Finally, Léa Collet's resolutely hybrid installation Digitalis (2024) revolves around a fiction in which artificial intelligence is the solution rather than the problem, enabling a symbiosis between humans and flowers. This very recent work by an emerging artist embodies the desire of an entire generation to reconcile with nature.

At Jeu de Paume

Hito Steyerl, Mechanical Kurds, 2025.

The Jeu de Paume has entrusted the general curatorship of the exhibition Le monde selon l'AI to Antonio Somaini, a researcher in theory of cinema, media and visual culture. The exhibition is divided into sections, ranging from analytical AI to generative AI, to tackle societal issues, as in the case of the video installation Mechanical Kurds (2025) by artist Hito Steyerl. The title refers to the 18th-century automaton that inspired Amazon to create its micro-work platform, as well as to the workers of the click. For it takes humans - in this case Kurds on micro-wages - to inform the machine, as was already the case with the Mechanical Turk.

Agnieszka Kurant, Aggregated Ghost, 2020.

Agnieszka Kurant, for her part, gives a face to this working class of invisible people, generally recruited from the global South. For the Aggregated Ghost print merges photographic portraits of those whom the artist has solicited. Here, artificial intelligence is on the side of the tool in the use of neural networks, as well as on that of the subject from a social point of view.

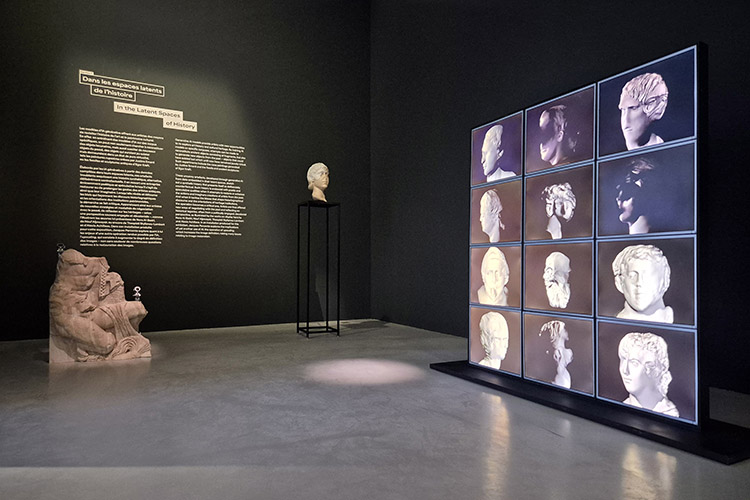

Egor Kraft, Content Aware Studies, 2018.

The section dedicated to "latent spaces in history" starts with the body of work Content Aware Studies, initiated in 2018 by Egor Kraft. He has focused on Greco-Roman sculpture, filling in the gaps and imagining alternatives. The contemporary contribution of artificial intelligence to archaeology echoes that of pioneering photography to the same discipline.

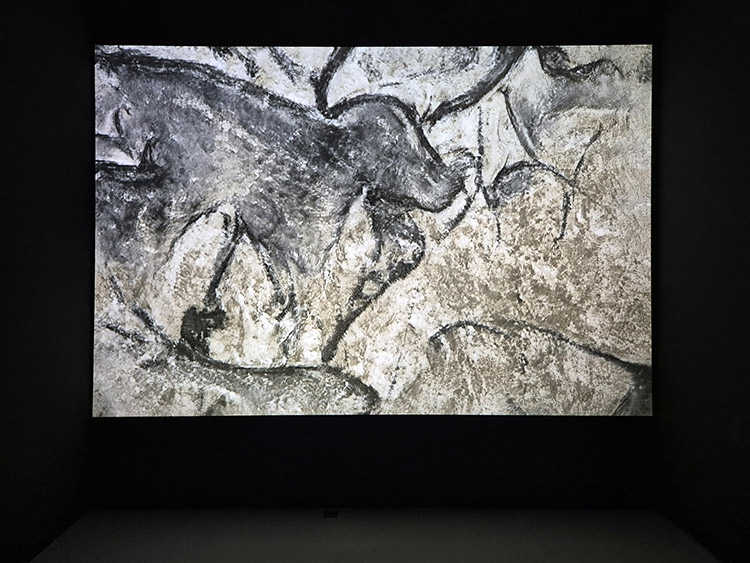

Justine Emard, Hyperphantasia, 2022.

Let's continue our journey back in time with Justine Emard, who has used generative antagonistic networks to imagine infinite variations on the Paleolithic drawings in the Chauvet cave. By extracting from latent space representations that will never know rock, the artist reveals the artificial dreams of a machine in her 2022 video sequence Hyperphantasia.

Grégory Chatonsky, La Quatrième Mémoire, 2025.

The generative film in Grégory Chatonsky's installation La Quatrième Mémoire (2025) brings together multiple alternative versions of himself. But this real-time sequence is only one component of what the artist has imagined as a tomb. It's up to the archaeologists of the futur to study the life he has lived, without dissociating it from the lives that inspired the machine and he could have lived.

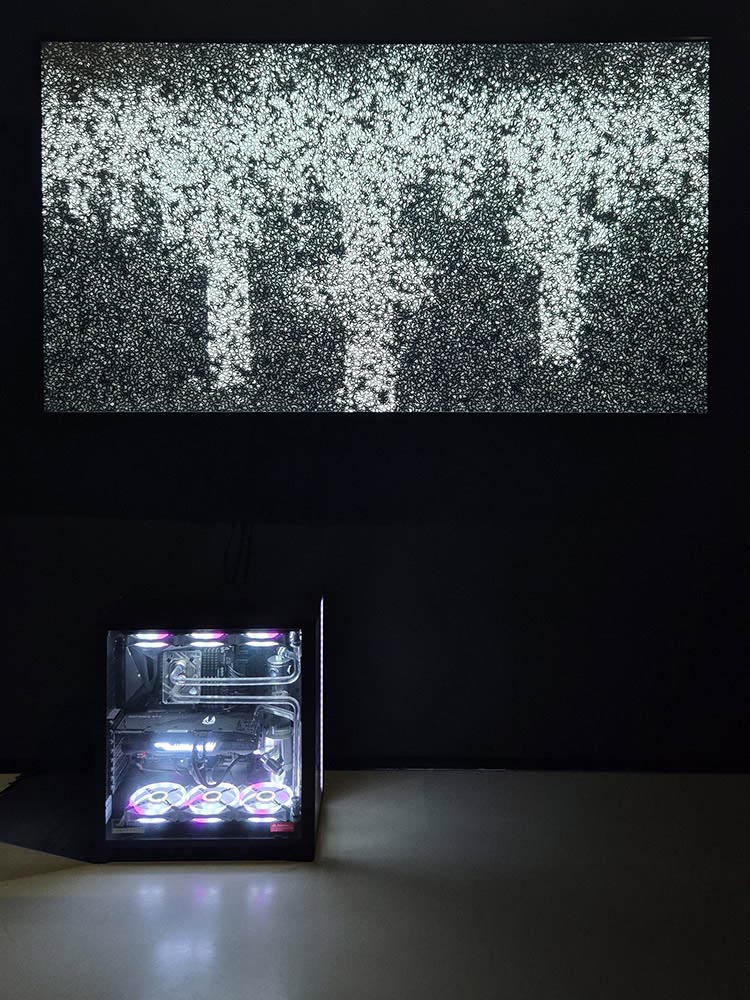

Samuel Bianchini, Prendre vie(s), version 03, 2020-2025.

Finally, there's Samuel Bianchini's Prendre vie(s) installation (2020), which, by displaying a computer tower, tells us that it too runs in real time. The strange, evolving granularity hints at the image of a cemetery summoning death. Although its display is the consequence of the operation of a cellular automaton entitled The Game of Life by its inventor John Horton Conway in 1970. It's a zero-player mathematical simulation game that many will discover among the many other notions and concepts explored in this exhibition at the crossroads of art, science and technology.

Articles

- Paris Photo

- Art, technology and AI

- Immersive Art

- Chroniques Biennial

- 7th Elektra Biennial

- 60th Venice Biennial

- Endless Variations

- Multitude & Singularity

- Another perspective

- The Fusion of Possibilities

- Persistence & Exploration

- Image 3.0

- BioMedia

- 59th Venice Biennale

- Decision Making

- Intelligence in art

- Ars Electronica 2021

- Art & NFT

- Metamorphosis

- An atypical year

- Real Feelings

- Signal - Espace(s) Réciproque(s)

- On Combinations at Work

- Human Learning

- Attitudes and forms by women

- Ars Electronica 2019

- 58th Venice Biennale

- Art, Technology and Trends

- Art in Brussels

- Plurality Of Digital Practices

- The Chroniques Biennial

- Ars Electronica 2018

- Montreal BIAN 2018

- Art In The Age Of The Internet

- Art Brussels 2018

- At ZKM in Karlsruhe

- Lyon Biennale 2017

- Ars Electronica 2017

- Digital Media at Fresnoy

- Art Basel 2017

- 57th Venice Biennial

- Art Brussels 2017

- Ars Electronica, bits and atoms

- The BIAN Montreal: Automata

- Japan, art and innovation

- Electronic Superhighway

- Lyon Biennale 2015

- Ars Electronica 2015

- Art Basel 2015

- The WRO Biennale

- The 56th Venice Biennale

- TodaysArt, The Hague, 2014

- Ars Electronica 2014

- Basel - Digital in Art

- The BIAN Montreal: Physical/ity

- Berlin, festivals and galleries

- Unpainted Munich

- Lyon biennial and then

- Ars Electronica, Total Recall

- The 55th Venice Biennale

- The Elektra Festival of Montreal

- Digital practices of contemporary art

- Berlin, arts technologies and events

- Sound Art @ ZKM, MAC & 104

- Ars Electronica 2012

- Panorama, the fourteenth

- International Digital Arts Biennial

- ZKM, Transmediale, Ikeda and Bartholl

- The Gaîté Lyrique - a year already

- TodaysArt, Almost Cinema and STRP

- The Ars Electronica Festival in Linz

- 54th Venice Biennial

- Elektra, Montreal, 2011

- Pixelache, Helsinki, 2011

- Transmediale, Berlin, 2011

- The STRP festival of Eindhoven

- Ars Electronica repairs the world

- Festivals in the Île-de-France

- Trends in Art Today

- Emerging artistic practices

- The Angel of History

- The Lyon Biennial

- Ars Electronica, Human Nature

- The Venice Biennial

- Nemo & Co

- From Karlsruhe to Berlin

- Media Art in London

- Youniverse, the Seville Biennial

- Ars Electronica, a new cultural economy

- Social Networks and Sonic Practices

- Skin, Media and Interfaces

- Sparks, Pixels and Festivals

- Digital Art in Belgium

- Image Territories, The Fresnoy

- Ars Electronica, goodbye privacy

- Digital Art in Montreal

- C3, ZKM & V2

- Les arts médiatiques en Allemagne

- Grégory Chatonsky

- Le festival Arborescence 2006

- Sept ans d'Art Outsiders

- Le festival Ars Electronica 2006

- Le festival Sonar 2006

- La performance audiovisuelle

- Le festival Transmediale 2006

- Antoine Schmitt

- Eduardo Kac

- Captations et traitements temps réel

- Maurice Benayoun

- Japon, au pays des médias émergents

- Stéphane Maguet

- Les arts numériques à New York