Multitude & Singularity

Multitude & Singularity, 2023-2024. Source Florian Kleinefenn.

Two notions that gained currency with the start of the new millennium are the multitude – the crowd made up of people connected with each other via networks – and technological singularity – the idea that machines will eventually become superior to human beings. In fact, the notions of multitude and singularity can be applied to both human beings and technologies. When we think of the multitude, we imagine our democratic commitments converging on social media, but we could just as well use the term to refer to the mass of data fed to the AI programs that are currently the focus of everyone’s attention. The singularity that concerns us is the online identities or profiles we are constantly tweaking, when we should be devoting as much attention to the concept of technological singularity, which raises questions about our relationship with the machines on which we are becoming increasingly dependent. The artworks assembled in the exhibition Multitude & Singularity at the Bicolore of the Maison du Danemark reflect the complexity of the world in its digital guise.

Multiple viewpoints

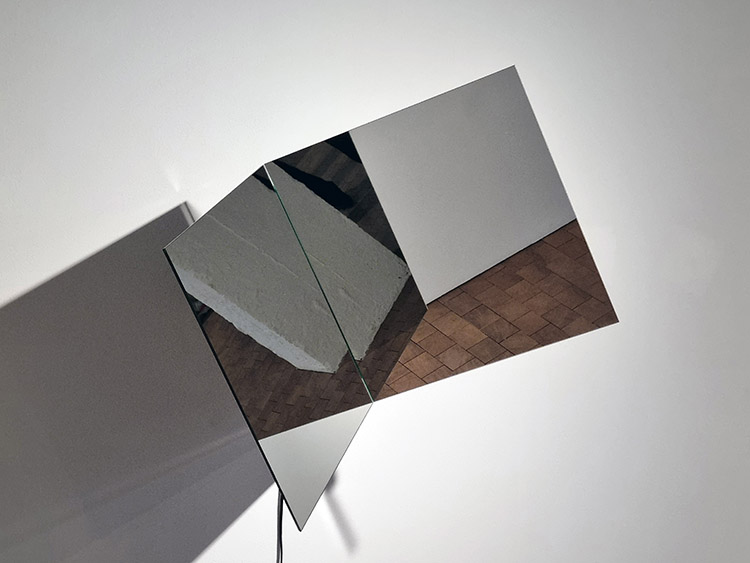

Jeppe Hein, 360° Illusion IV, 2008.

Jeppe Hein is an artist whose medium is perception. He often uses reflecting surfaces, as in 360° Illusion IV. Mirrors undeniably attract us, wherever they are – including in art centers and museums. But Hein’s rotating mirror is especially fascinating because it questions the notion of the viewpoint, a recurrent concept in the history of art. Rather than reflecting our image, the rotating object before our eyes reflects two viewpoints, like two co-existing states of the world, simultaneously alluding to quantum physics and turning this participatory artwork into a laboratory experiment. Hein’s approach is often comparable to scientists’ use of reflecting surfaces in their research laboratories, and the gaze of the public is a vital component of his installations.

Listening to the invisible

Jens Settergren, GhostBlind Loading, 2021.

As our household appliances increasingly become connected, we tend to think of them as intelligent, crediting them with an indefinable extra something. Jens Settergren recorded the sounds made by technical objects in our everyday surroundings, processed them and then slipped them into the immersive soundscape GhostBlind Loading. Music made up of sounds we scarcely register as a rule is played via speakers that look like rocks, which are readily available from big retailers. This ghostly presence prompts us to reconsider the electromagnetic activities of the invisible presences with which, unbeknownst to us, we share our lives. The presence of camouflage huts with reflecting surfaces gives viewers the feeling they are being watched – a feeling we are increasingly experiencing even in our own homes, with the onward march of connectedness. The notions of invisibility and surveillance are indissociable both in our collective imagination and in the everyday reality of our lives.

Terrors

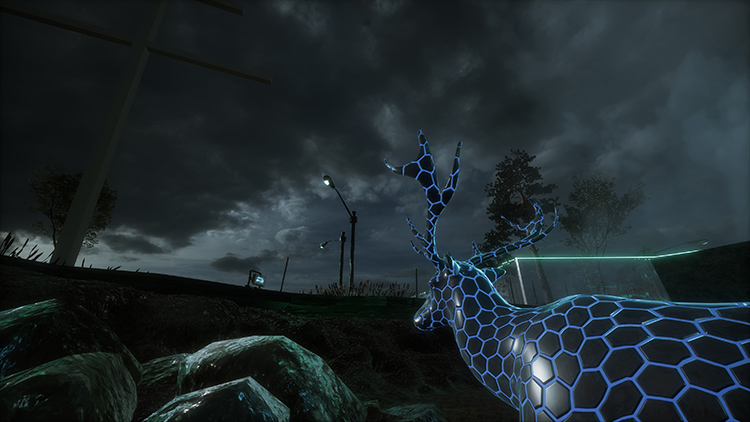

Jakob Kudsk Steensen, Aquaphobia, 2017.

Jakob Kudsk Steensen creates artificial worlds for poetic narratives in the form of virtual reality experiences, video games or film sequences. His inspiration for the 3D sequence Aquaphobia came from psychological studies of treatments for fear of water – not forgetting that people can also be afraid of not having enough water or of excess water, as flooding threatens more and more places. In the world of Aquaphobia, we are guided by a liquid entity, perhaps in reference to the fact that our bodies consist chiefly of water. This body with its changing contours, which leads us from underground to the surface, is disturbing rather than menacing, especially as it is accompanied by a soothing voice literally off. Via several dim tunnels, we come to a place that recalls Brooklyn when it was flooded by Hurricane Sandy in 2012. In Jakob Kudsk Steensen’s work, the imaginary creation never completely distances itself from its real-life inspiration.

Between real and virtual

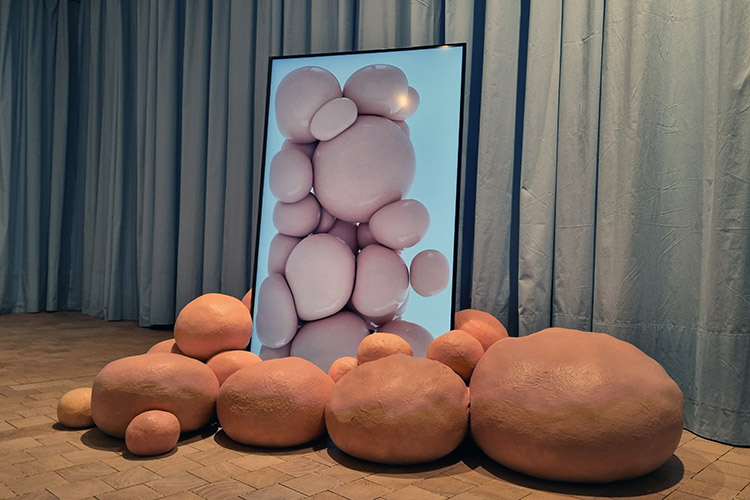

Stine Deja & Marie Munk, Synthetic Seduction, 2018.

When Stine Deja and Marie Munk work together, their aesthetic senses converse and intertwine. In this installation from the series Synthetic Seduction, the objects on the floor seem to be continued in the on-screen image – unless it is the opposite – prompting us to reflect on how the sculptures and images differ and how they are alike, thereby gaining insights into their nature. Their roundness tells us they are organic, and their flesh-pink color suggests skin. On the floor, they are static, but in the space of the image, where the frame restricts their movements, their materiality is somewhat different. If the floor sculptures of varying sizes had come out of the screen and invaded the tangible space of the exhibition, they would have lost some of their virtual sheen in the process and become more strongly present. It is as if everything took place in the interstice between objects and their depictions, even when the latter are three-dimensional, with no way of knowing which direction they might move in.

Artificial emotions

Stine Deja & Marie Munk, Synthetic Seduction: Skin-to-Skin, Foreigner, 2018.

In a hospital-like setting bounded by a blue curtain, Stine Deja and Marie Munk invite us to take our seats on a sculpture with the texture of skin. Seemingly organic, it responds to touch as if to simulate life. Comfortably seated Skin-to-Skin – one artificial, the other real – we watch the 3D sequence Foreigner, which is about artificial intelligence. The being that appears to be seeing its own face for the first time in a wake-up room seems to be endowed with consciousness but to have no experience. At least, that is what the 1980s song whose chorus “I want to know what love is” the being bursts into suggests in this context. The question of whether artificial beings can feel is a trope of twentieth-century science-fiction. It becomes crucial in the research laboratories in which conversational robots emerge, in need of a body but without experience. In the process of giving shape to their ideas, the two artists explore the issue of posthumanism. After all, fiction is often ahead of science.

What the machine sees

Cecilie Waagner Falkenstrøm, An algorithmic gaze II, 2023.

For centuries, artists have learned how to depict the human body by drawing naked bodies. So, it’s hardly surprising we’ve ended up teaching machines the same way. But there is a problem. It is not so much to do with the algorithms themselves as with the data fed to them. There has been an overriding tendency to supply them exclusively with visuals portraying a notional Western human being. Waagner Falkenstrøm has tried to get over this bias by collecting thousands of nude photographs that reflect our diversity in terms of gender, age, and ethnicity. With a learning process of this kind, it’s easy to suppose that the machine will tend to depict a person who is an overall composite, a hybrid of all of us. In fact, it keeps endlessly attempting to do so, generating thousands of depictions in which we might all recognize bits of ourselves here or there. But it is the monstrosities it occasionally comes up with that most makes us wonder how it sees us.

The technological other

Mogens Jacobsen, No Us (but 1 Off), 2023.

Mogens Jacobsen’s installation No Us (but 1 Off) is made up of dedicated entrance, processing and exit apparatus. First, there is a sort of mirror-cum-screen through which visitors literally enter the artwork, which revolves around an AI program that “invents” faces based on those of the viewers so that the artwork is generated as they watch. The artist turns the exhibition space, as it were, into his studio, while the machine creates portraits in which we cannot tell how much is real, reinforcing the idea that our selves are constructed via interactions with the other in this era when the other is increasingly a technological entity. A final point worth noting is that the artist has opted to broadcast all his countless portraits via an audiovisual technique that harks back to the beginnings of television. Is this a way of telling us that in terms of artificial intelligence, we have a very long way to go, while AI has lately become one of us?

Articles

- Paris Photo

- Art, technology and AI

- Immersive Art

- Chroniques Biennial

- 7th Elektra Biennial

- 60th Venice Biennial

- Endless Variations

- Multitude & Singularity

- Another perspective

- The Fusion of Possibilities

- Persistence & Exploration

- Image 3.0

- BioMedia

- 59th Venice Biennale

- Decision Making

- Intelligence in art

- Ars Electronica 2021

- Art & NFT

- Metamorphosis

- An atypical year

- Real Feelings

- Signal - Espace(s) Réciproque(s)

- On Combinations at Work

- Human Learning

- Attitudes and forms by women

- Ars Electronica 2019

- 58th Venice Biennale

- Art, Technology and Trends

- Art in Brussels

- Plurality Of Digital Practices

- The Chroniques Biennial

- Ars Electronica 2018

- Montreal BIAN 2018

- Art In The Age Of The Internet

- Art Brussels 2018

- At ZKM in Karlsruhe

- Lyon Biennale 2017

- Ars Electronica 2017

- Digital Media at Fresnoy

- Art Basel 2017

- 57th Venice Biennial

- Art Brussels 2017

- Ars Electronica, bits and atoms

- The BIAN Montreal: Automata

- Japan, art and innovation

- Electronic Superhighway

- Lyon Biennale 2015

- Ars Electronica 2015

- Art Basel 2015

- The WRO Biennale

- The 56th Venice Biennale

- TodaysArt, The Hague, 2014

- Ars Electronica 2014

- Basel - Digital in Art

- The BIAN Montreal: Physical/ity

- Berlin, festivals and galleries

- Unpainted Munich

- Lyon biennial and then

- Ars Electronica, Total Recall

- The 55th Venice Biennale

- The Elektra Festival of Montreal

- Digital practices of contemporary art

- Berlin, arts technologies and events

- Sound Art @ ZKM, MAC & 104

- Ars Electronica 2012

- Panorama, the fourteenth

- International Digital Arts Biennial

- ZKM, Transmediale, Ikeda and Bartholl

- The Gaîté Lyrique - a year already

- TodaysArt, Almost Cinema and STRP

- The Ars Electronica Festival in Linz

- 54th Venice Biennial

- Elektra, Montreal, 2011

- Pixelache, Helsinki, 2011

- Transmediale, Berlin, 2011

- The STRP festival of Eindhoven

- Ars Electronica repairs the world

- Festivals in the Île-de-France

- Trends in Art Today

- Emerging artistic practices

- The Angel of History

- The Lyon Biennial

- Ars Electronica, Human Nature

- The Venice Biennial

- Nemo & Co

- From Karlsruhe to Berlin

- Media Art in London

- Youniverse, the Seville Biennial

- Ars Electronica, a new cultural economy

- Social Networks and Sonic Practices

- Skin, Media and Interfaces

- Sparks, Pixels and Festivals

- Digital Art in Belgium

- Image Territories, The Fresnoy

- Ars Electronica, goodbye privacy

- Digital Art in Montreal

- C3, ZKM & V2

- Les arts médiatiques en Allemagne

- Grégory Chatonsky

- Le festival Arborescence 2006

- Sept ans d'Art Outsiders

- Le festival Ars Electronica 2006

- Le festival Sonar 2006

- La performance audiovisuelle

- Le festival Transmediale 2006

- Antoine Schmitt

- Eduardo Kac

- Captations et traitements temps réel

- Maurice Benayoun

- Japon, au pays des médias émergents

- Stéphane Maguet

- Les arts numériques à New York