Image 3.0

The IMAGE 3.0 exhibition at the Cellier in Reims, organised by the curators Quentin Bajac and Pascal Beausse, is the result of a joint photographic commission from the Centre national des arts plastiques and the Jeu de Paume. The practices brought together here question representation as much as gaze in this digital age.

Utopia

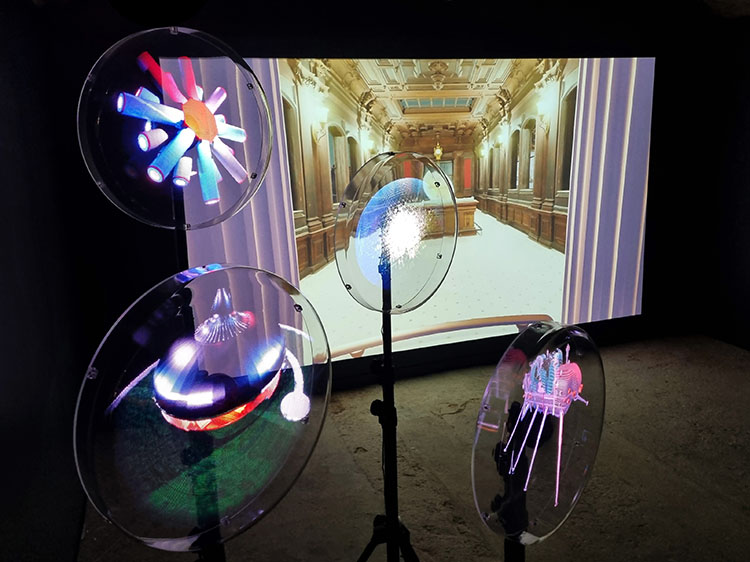

Donatien Auber, La Cybernétique, le vivant et la ville, 2021.

Cybernetician Norbert Wiener's statement at the beginning of the three-dimensional sequence entitled Cybernetics, the Living and the City by Donatien Auber is relatively pessimistic: "In a very real sense we are shipwrecked passengers on a doomed planet" (1952). The great fears of the 20th and 21st centuries, from nuclear winter to environmental collapse, are evoked here through the movements of a virtual camera crossing the ages, from ancient Greece to the present day. However, it is the extreme technological creativity that the artist celebrates with this same sequence that is augmented by holographic propellers. It is as if the great fears were also at the origin of the most beautiful utopias and that the living, more threatened today than ever, was the most perfect model for technoscience.

Imagination

Brodbeck & de Barbuat, Les 1000 vies d’Isis, 2021.

Fear is also what prompts some children to invent imaginary friends. This is precisely what Brodbeck & de Barbuat have done in computing The 1000 Lives of Isis. It is a series of framed prints which emphasise the idea of the photographic medium. But we find in these the image of a person that they entirely conceived in advance of their software applications computing her. She evolves in various situations allowing us to better understand her in this era where such presences are multiplying on Instagram. The idea of inventing bodies that nature could not create is not new if we consider Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’ nude La Grande Odalisque (1814). The artist did not hesitate to augment the body of his model with a few extra vertebrae. Conversely, the duo wanted Isis to be perfectly "human" to unfold her story in representations that are only photographic in their reference.

Simulacrum

Philippe Durand, Gour de Tazenat, 2021.

The question of the photographic is central to this exhibition at the Cellier in Reims. So much so that one regularly doubts the exact nature of the works, as is the case with Philippe Durand's series of images. There is something that catches the eye without one knowing whether it is the textures or lights of the stones emerging from the Gour de Tazenat. It is interesting to note that ‘gours’, in the various regions of France, are often accompanied by myths or legends evoking magic, and here, the artist's stones seem to emerge from the water. It is only when we allow our eyes to explore the surfaces, which we thought were flat, that we realise the simulacra. The stones are in fact treated differently using a technique created in a research and development laboratory where the magic of technology is also at work.

Uncertainty

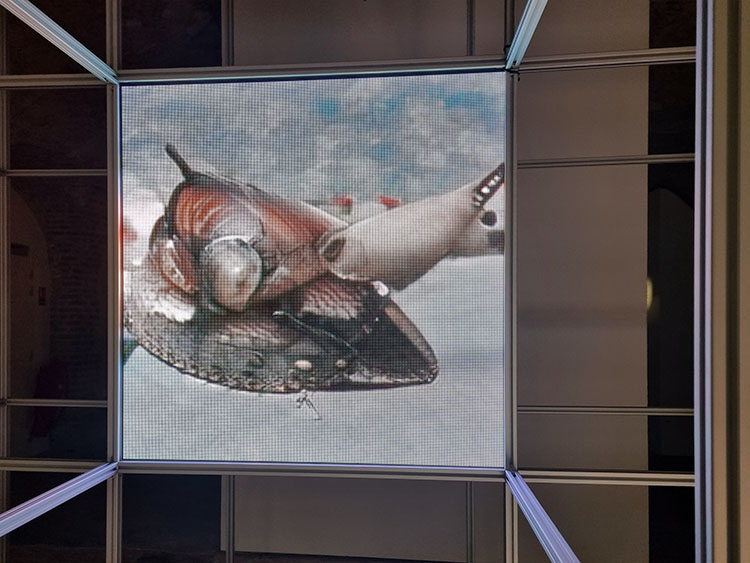

Grégory Chatonsky, Complétion, 2021.

We must recognise that by ‘subcontracting’ the creation of their images entirely to artificial intelligence algorithms, and more precisely to artificial neural networks in the case of Grégory Chatonsky, the artists summon this same magic of technology. He himself is unaware of the forms that will emerge from such processes, and the synthetic voice he has trained to describe them also seems to have doubts. The aesthetic that the artist develops in his installation Complétion is one of uncertainty. No one will see all the photographs that scroll across an LED screen as the algorithm itself cannot anticipate the images it produces on a second screen based on the rules that constitute the essence of Gregory Chatonsky's artistic gesture at the origin of a quintessentially autonomous narrative. That is to say, it escapes both human and machine control.

Control

Justine Emard, Neurosynchronia, 2021.

The experience begins when white noise, in which we observe only a few trackers, dissipates and, after the time needed to calibrate the device with which we are equipped, we concentrate on zones of the image in order to navigate with our minds from one scene to another. This is no longer a matter of interaction, but rather a form of control that only involves thought. Attention, which is economy online, is at work here in which the immobility conducive to concentration and contemplation is de rigueur. The idea that we can act on our environment with our mind without unnecessary gesticulation is striking. There is something of the order of shamanism in this journey entitled Neurosynchronia that Justine Emard proposes to take us on. When, literally, we teleport from place to place in a relative darkness that intensely serves the suspense and refers to the universe of dreams that we never manage to control.

Attention

Raphaël Dallaporta, Volatility Index, 2020.

Attention is also at the centre of Raphaël Dallaporta's installation Volatility Index. But it is our own reflection that we observe via a mirror associated with the device that quantifies it. The sound of the device, comparable to those of the cash registers in our supermarkets, inevitably draws our attention. This has the effect of interrupting the experiment. It is as if the observation of the result of the experiment irreparably distorts it. This brings to mind laboratory experiments that do not tolerate observation that could alter the measurements. As for the mirror, it perfectly symbolises the screens that, the more we observe, the more they reflect our personalities while making the fortune of companies deploying highly personalised content. For if in art the gaze makes the artwork, it is also at the centre of all attention, well beyond the sphere of art.

Articles

- Ososphère

- Paris Photo

- Art, technology and AI

- Immersive Art

- Chroniques Biennial

- 7th Elektra Biennial

- 60th Venice Biennial

- Endless Variations

- Multitude & Singularity

- Another perspective

- The Fusion of Possibilities

- Persistence & Exploration

- Image 3.0

- BioMedia

- 59th Venice Biennale

- Decision Making

- Intelligence in art

- Ars Electronica 2021

- Art & NFT

- Metamorphosis

- An atypical year

- Real Feelings

- Signal - Espace(s) Réciproque(s)

- On Combinations at Work

- Human Learning

- Attitudes and forms by women

- Ars Electronica 2019

- 58th Venice Biennale

- Art, Technology and Trends

- Art in Brussels

- Plurality Of Digital Practices

- The Chroniques Biennial

- Ars Electronica 2018

- Montreal BIAN 2018

- Art In The Age Of The Internet

- Art Brussels 2018

- At ZKM in Karlsruhe

- Lyon Biennale 2017

- Ars Electronica 2017

- Digital Media at Fresnoy

- Art Basel 2017

- 57th Venice Biennial

- Art Brussels 2017

- Ars Electronica, bits and atoms

- The BIAN Montreal: Automata

- Japan, art and innovation

- Electronic Superhighway

- Lyon Biennale 2015

- Ars Electronica 2015

- Art Basel 2015

- The WRO Biennale

- The 56th Venice Biennale

- TodaysArt, The Hague, 2014

- Ars Electronica 2014

- Basel - Digital in Art

- The BIAN Montreal: Physical/ity

- Berlin, festivals and galleries

- Unpainted Munich

- Lyon biennial and then

- Ars Electronica, Total Recall

- The 55th Venice Biennale

- The Elektra Festival of Montreal

- Digital practices of contemporary art

- Berlin, arts technologies and events

- Sound Art @ ZKM, MAC & 104

- Ars Electronica 2012

- Panorama, the fourteenth

- International Digital Arts Biennial

- ZKM, Transmediale, Ikeda and Bartholl

- The Gaîté Lyrique - a year already

- TodaysArt, Almost Cinema and STRP

- The Ars Electronica Festival in Linz

- 54th Venice Biennial

- Elektra, Montreal, 2011

- Pixelache, Helsinki, 2011

- Transmediale, Berlin, 2011

- The STRP festival of Eindhoven

- Ars Electronica repairs the world

- Festivals in the Île-de-France

- Trends in Art Today

- Emerging artistic practices

- The Angel of History

- The Lyon Biennial

- Ars Electronica, Human Nature

- The Venice Biennial

- Nemo & Co

- From Karlsruhe to Berlin

- Media Art in London

- Youniverse, the Seville Biennial

- Ars Electronica, a new cultural economy

- Social Networks and Sonic Practices

- Skin, Media and Interfaces

- Sparks, Pixels and Festivals

- Digital Art in Belgium

- Image Territories, The Fresnoy

- Ars Electronica, goodbye privacy

- Digital Art in Montreal

- C3, ZKM & V2

- Les arts médiatiques en Allemagne

- Grégory Chatonsky

- Le festival Arborescence 2006

- Sept ans d'Art Outsiders

- Le festival Ars Electronica 2006

- Le festival Sonar 2006

- La performance audiovisuelle

- Le festival Transmediale 2006

- Antoine Schmitt

- Eduardo Kac

- Captations et traitements temps réel

- Maurice Benayoun

- Japon, au pays des médias émergents

- Stéphane Maguet

- Les arts numériques à New York